A worldwide and well-known high-tech company in Japan has tested a shorter work week. The results were positive, but the experiment was short, only lasting a few months in the summer. Iceland, on the other hand, did a similar trial that lasted over a full four-year period, involving 1% of the country’s entire population, the results were similar.

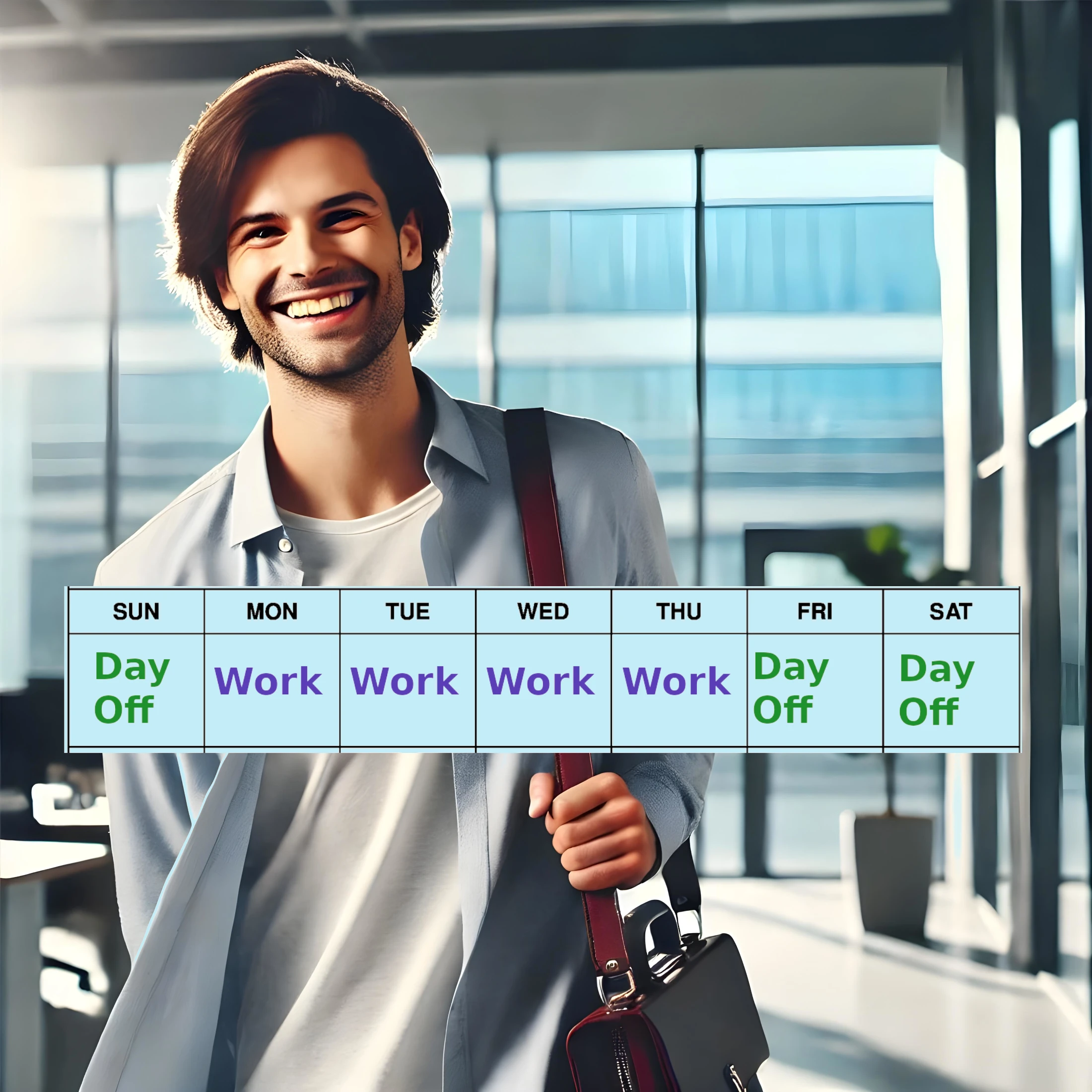

The tech company in Japan offered 2,300 workers a four-day work week. The workers got the same amount of pay as their usual five-day work week. This was a big deviation from Japan’s well known overtime work culture.

The results were astounding, leading to a 40% increase in productivity. Employees reported experiencing better work–life balance and improved focus in the office. “I had more time for exercise, running errands, and being with my family” says one employee, “My mind was more rested which increased my focus and my motivation at work.”

An unplanned side effect of the trial—the company saved almost 30% on electricity since the offices were closed an extra day per week. Also, all meetings were cut to under 30 minutes. The test-run resulted in increased worker productivity, a decrease in expenses, and a happier workforce.

There have been many companies who have tested shorter work weeks with great results. But short trials can be deceiving. It’s easy to change people’s behaviors over the short-term. But in the long-term people may adjust. They might get used to their situation and productivity may begin to fall, and this is what makes the Iceland study so important.

The Iceland study took place over a full four year period, involving more than 2,500 workers, which amounts to about 1% of Iceland's working population. A range of workplaces took part, including preschools, offices, social service providers, and hospitals.

The results were similar to that of Japan’s trial, with worker productivity either increasing or staying the same. Shorter work-weeks translated into increased well-being of employees including less life stress, and less worker burnout, which all leads to more mental alertness at work.

The benefits clearly fit the worker, but it also benefits the organization as well. These are great results for companies that are considering shorter hours, remote work, or more flexible work schedules.

“It’s really simple to me,” says Jack Tormay, a worker in the study. “People say, you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink. Well, you can make people come to the office for longer periods of time, but you can’t make them more productive. People have a productivity limit. There’s only so much they can mentally or physically do in a day’s time. If you make me come in more, then I’ll take more small breaks, have longer coffee breaks, and more frequent chats with my co-workers. I’ll take longer lunches, come to work late, and sneak out early.”

Flack Sparrow, Tormay’s boss, agrees. “So the shorter hours mean more focused work time, fewer and shorter breaks, and more motivation to get the job done and enjoy your free time, not to mention the reality of needed mental rest.”